Day after day, the victims of the Hamas terror attacks arrive at the National Center of Forensic Medicine in Tel Aviv.

For the scientists trying to identify them, it’s heavy work and it’s getting a lot harder.

Warning: This report contains images of human remains and graphic descriptions of injuries – which some people might find distressing

It’s not full corpses they are receiving anymore, but charred fragments of bones.

Many of those killed were mutilated, their bodies burned and it is harrowing work for the team to try and identify them.

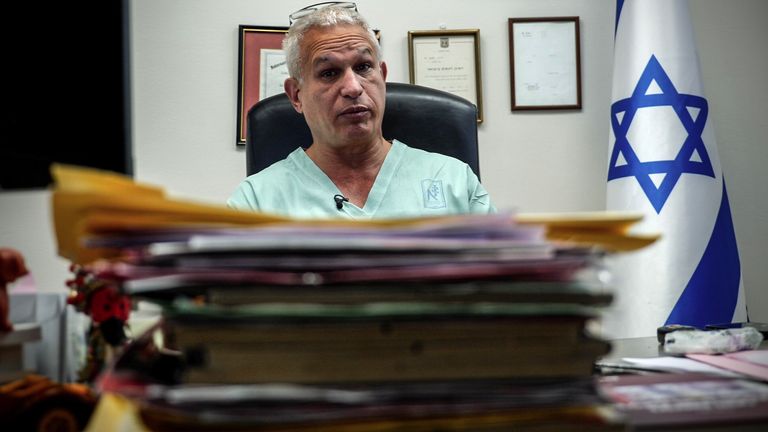

Chen Kugel, the director of the centre, greets us with warmth and a smile.

It is amazing he’s able to muster one.

He hasn’t stopped for weeks.

But when he finally does, he breaks down, distressed at the growing realisation that there are some individuals they just won’t be able to identify.

Follow live: Blinken in West Bank for first time since war

“Professionally I want to bring every one of them to the grave to give them the last honour,” he tells me, as his eyes fill with tears.

He, like everyone here, feels a huge sense of duty to the families to provide them with news and hopefully, some closure.

Mr Kugel has witnessed a pattern of brutality that haunts him and it’s on a massive scale.

As we sit in his office, he starts to show us a series of images that highlight the extreme barbarity of the attack on 7 October by Hamas, which triggered the latest conflict.

“So many bodies were shot. But before they were shot, they were cuffed for execution style.”

Some have stab wounds, others have their hands tied with electric cables.

There is a child beheaded.

He shows us one image of a victim with stab wounds on his back and head.

“You can see that the pelvis is shattered. These are bullets inside. So he was shot, he was stabbed, he was burned. And then he was run over by a car.”

It is stomach-turning.

I too feel my eyes fill with tears as I look at the horrendous nature of some of the injuries.

Many of the bodies were burned.

“It’s like a crematorium,” he says.

It’s bleached the bones.

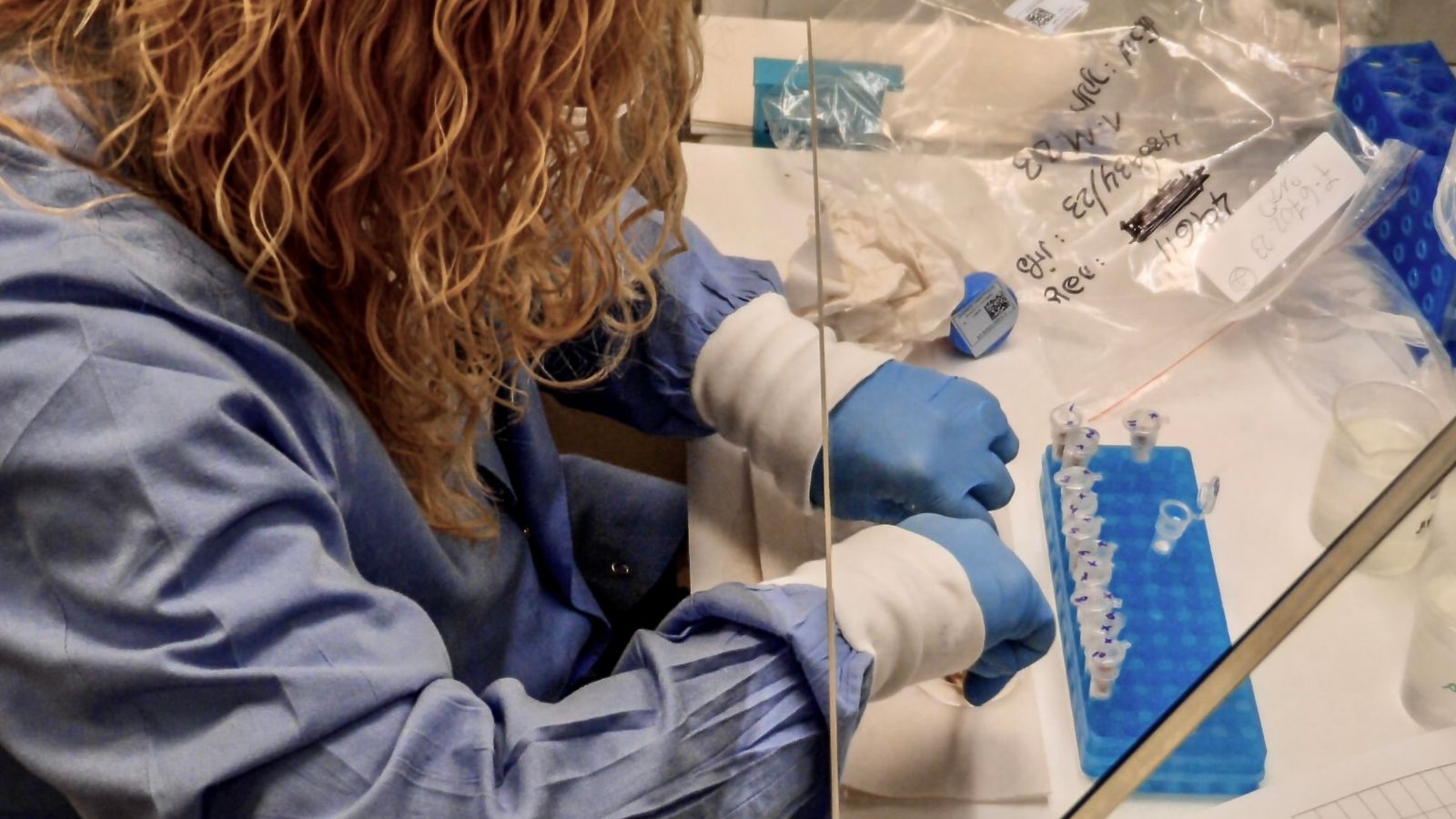

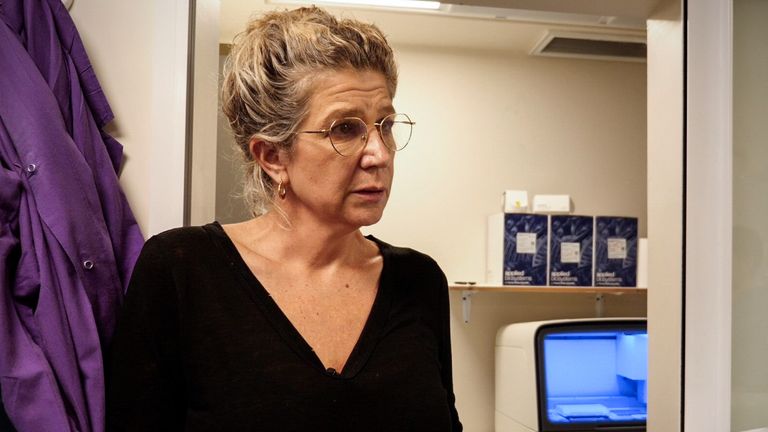

Downstairs, Dr Nurit Bublil is looking at some of the toughest cases.

She’s in charge of the DNA lab where they’re looking at tiny bits of tissue.

But it’s a large item of evidence that stops her in her tracks – and me.

She lifts a bag and shows me a baby’s mattress. It’s covered in blood.

“This baby was probably stabbed in his own bed.”

You can hear rage in Dr Bublil’s tone as she describes the attackers.

“This is just genocide. For hours, they slaughtered our people and they enjoyed every minute of it.”

On the ground floor, we meet Michal Peer, an anthropologist.

She shows us boxes she says are filled with debris, metal, glass and even pieces of mobile phones that people were holding onto at the time.

Her job she says is to separate out the bones from the non-bones and try to trace who they might belong to.

She’s only 30-years-old.

Read more:

Inside Gaza with Israeli troops

Blinken ‘committed’ to establishment of Palestinian state

Israeli minister suspended after saying dropping nuclear bomb on Gaza ‘one of the possibilities’

“Before this event, I had never had to deal with the remains of children,” she says.

“This is the first time and it’s really difficult.

“It’s hard to disconnect from it, but you have to because even if it’s the smallest piece of bone that we can send up to the lab for them to try to pull a DNA profile, that’s the whole reason I got into this field, for the families who are looking for their loved ones and wanting to know what happened to them.

“I want to let those families have the chance to give their loved ones a proper burial.”

It is slow, detailed, technical work and it is vital, for the families and the nation.