GUARUJA, Brazil — Charles Oliveira slowly climbs the paved steps of Morro do Maluf, a cliff overlooking the Brazilian coastal city where he grew up. He rests his arms on a metal railing and basks in the view of the city’s skyline and the beach that stretches miles north, toward Rio de Janeiro.

“Look at this,” he says, to no one in particular. “Look at what God has given us.”

Oliveira, who will take on surging lightweight contender Arman Tsarukyan at UFC 300 on Saturday (10 p.m. ET on ESPN+ PPV), has been coming to this cliff his entire life. In addition to its stunning view of the water, Morro do Maluf offers a stark look at something else. As in most areas of Sao Paulo, there is a wide income disparity in Guaruja, and Oliveira can see it from this cliffside — a long line of luxury resorts on the beach, flanked by poverty-stricken neighborhoods called favelas working inland. In 2004, Brazilian photojournalist Tuca Vieira captured a famous image of this wealth divide — a penthouse residential complex and a Brazilian slum, separated by a single wall.

Most people born here know only one of these two realities: Either you enter the world with the resources to create a life for yourself, or you don’t.

Oliveira is one of the very few who has lived on both sides. He was born into poverty here in 1989. He grew up in a neighborhood just outside of Favela da Prainha and Favela do Caixão. He lived on a small dirt plot owned by his grandmother, along with his mother, father, two brothers, two aunts and uncle. His mother cleaned houses and his father worked in a local slaughterhouse. The family would save money for months just to be able to eat at a restaurant a few times a year.

For many of Oliveira’s peers, the path to a more prosperous life involved illegal drugs. Many of his former school classmates are either dead or incarcerated. His mother, Ozana, used to worry so much about her sons falling into that life, that she essentially put them on house arrest any time she wasn’t there.

“I would leave him with [his grandmother], and I would say, ‘Don’t let him go on the street,'” Ozana told ESPN. “[The drugs] were on the corner, they were on both sides of the street. When they would get home from school, I would check their heads and their bags. Their heads for the little bugs that would often get in there, and their bags for anything that wasn’t theirs. I always taught them to do the right thing.”

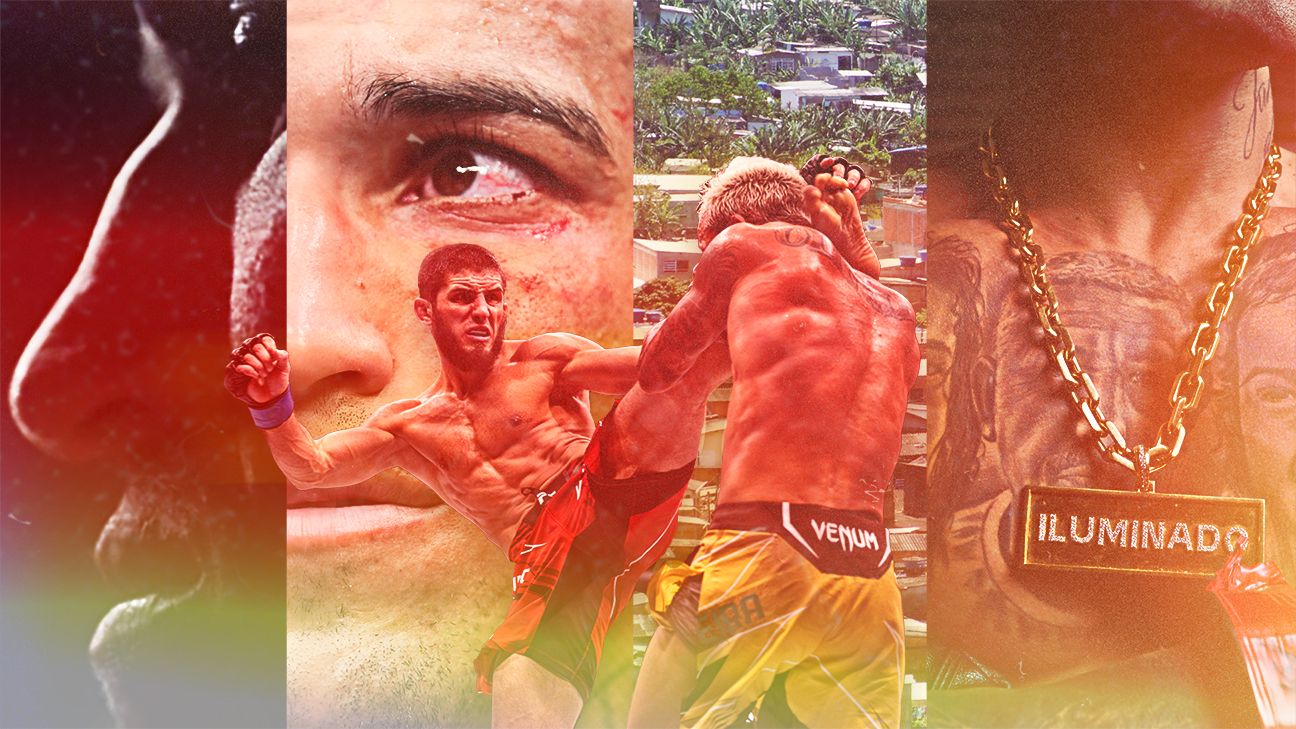

Oliveira, 33, is among the world’s most well-recognized and respected fighters. The word “illuminado” is tattooed under a pair of clasped hands in prayer on his neck. It means “enlightened” and represents Oliveira’s belief and trust in God. He believes God chose him specifically to shine in this world and rise above the life he was born into. Because if a higher power isn’t responsible for the improbabilities that have happened in his life, what else could explain it?

“My story is not something we made up,” Oliveira says. “My story happened. I’m a guy who came from the back of my grandmother’s house to everything I’m living today. I really believe that I am blessed, you know? I believe that God chose me to make history.”

Oliveira (34-9) will try to build upon that history this year. He was supposed to face Islam Makhachev (24-1) for the lightweight championship last October, but suffered a facial cut that forced him out of the fight just 12 days before it was scheduled. A title fight against Makhachev is still Oliveira’s goal, but now he must go through the additional challenge of Tsarukyan (21-3) to get there.

If he does beat Tsarukyan, he is likely to face an enormous challenge in Makhachev, ESPN’s No. 1 pound-for-pound fighter in the world. The two met in a championship fight in October 2022 in Abu Dhabi, and Makhachev dominated Oliveira, submitting him in the second round to claim his UFC belt. Oliveira’s performance was so poor that night that he has refused to watch it. He says he never will.

“He doesn’t watch that fight because it reminds him of the night he gave up,” Makhachev told ESPN.

Despite everything Oliveira has accomplished in his UFC career, it’s easy to think he will never hold a UFC title again. Tsarukyan, 27, is widely regarded as a future champ and is favored to beat Oliveira on Saturday (-225 on ESPN BET). And Makhachev has already proved to be a stylistic nightmare for Oliveira’s Muay Thai and submission-based skill set.

But if you stand alongside Oliveira at Morro do Maluf, it’s just as easy to believe there is no challenge he can’t overcome. Life has presented him with challenges far greater than anything he could see in an Octagon. For a kid who came from poverty and endured a serious medical condition in his youth, why can’t he beat the lightweight division’s brightest new contender in Tsarukyan and an invincible force in Makhachev? In his mind, the outcomes of these challenges have already been determined.

“My story has never been easy, so why would it be easy now?” Oliveira says. “My entire life, I have never had a problem believing. These are just tests. You want to be a champion? You have to overcome these tests. God has a plan.”

OLIVEIRA’S FAITH IN a higher power goes back his entire life, but his faith in being chosen by God to do something special with his life — to be “enlightened” — came when he was 18 years old, rooted in earlier experience.

When Oliveira was 8, he began feeling sharp pain in his bones whenever the weather changed. The suffering was so great at times that his father, Francisco, would carry him. Oliveira’s parents took him to the public hospital, the only facility they could afford, and spent years trying to diagnose the problem. Oliveira would go to the hospital, receive a few shots, stay for an extended period and be released, only for the issues to return.

“I was admitted for a long time, going in and out,” Oliveira says. “I think the doctors eventually would just give me a breather, you know? My mom would come stay with me when she could, but she had to work. I was a kid. I remember I tried to run away. Imagine me as a kid, locked up, spending time away from my parents.”

It wasn’t until a visiting physician saw Oliveira that a cause was determined for his pain. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disorder, and a heart murmur. He was placed on a regimen of shots every 15 to 21 days and told to refrain from all vigorous physical activity.

Oliveira agreed to the shots and even quit soccer, one of the first loves of his life. But when he was 12, a family friend introduced him to Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which became an obsession. It was immediately apparent Oliveira was a phenom on the mats, and within one month of training, Oliveira said he medaled in an open circuit.

“We went back to the doctor after that for a routine appointment, and I threw the medal on the table,” Oliveira recalls. “He was like, ‘What is this all about?’ My dad said, ‘He’s a jiu-jitsu champion.’ And the doctor said I shouldn’t do that, but my dad told him the whole story and he said, ‘Well, if it’s been good for him, then let him go.”

Oliveira would keep up the injections — and the jiu-jitsu — for six more years. When he was 18, however, he decided he’d had enough. The injections were painful, and he says they took away from his life as a “normal kid.” Nearly a decade of shots had taken a toll on his self-assuredness. He told his father he would never take another shot and live with the consequences. Francisco quickly got on board, however Ozana loathed the decision — especially with Oliveira exerting himself in martial arts.

“I said, ‘No, son, for God’s sake! Do you want to kill me?'” Ozana said. “And he said, ‘Mom, it won’t come back.’ I told him, ‘OK, son. If you want to do it, go ahead … but you already know, if you come back hurt, you have to deal with me.

“There is no explanation of what happened next.”

What happened next was nothing. No pain. No complications. When the weather shifted, Oliveira waited for that coinciding pain to come. It never did. He felt “normal” again, for the first time in 10 years.

“I told my dad that I’d rather die than continue taking those things,” Oliveira said. “It was around that time that I started to say, ‘I’m blessed by God.’ The doctors said I couldn’t even play soccer, you know? So, imagine out of nowhere, you decide to say, ‘I’m not taking anything else.’ I think from that moment on, I believed that God is with me and I had a huge bond with him.'”

Oliveira turned pro in MMA the same year he stopped taking the shots. Ozana waited with bated breath for his symptoms to return — along with any injury that might occur in MMA. But Oliveira’s health issues never returned, and his career blossomed. He signed with the UFC when he was 20 and went on to win the UFC’s lightweight title and set the record for the most submission wins in UFC history.

Before he ran into Makhachev, Oliveira had an air of invulnerability. He was knocked down in three consecutive title fights against top competition in Michael Chandler, Dustin Poirier, and Justin Gaethje, only to rally back and finish all three. Before Makhachev, he’d won 11 straight fights and established himself as one of the best fighters in the world.

But on the night of Oct. 22, 2022, Oliveira says he didn’t show up. He was ineffective against Makhachev and lost. He’s spent a lot of time over the past year trying to figure out what happened. Ultimately, the answer goes back to how he was able to stop taking injections at age 18 and walk away healthy. He believes something else was at work.

“I’ve tried to understand that fight,” Oliveira says. “Honestly, I think the man upstairs didn’t want me to win. I don’t know why. But we’re going to have a new meeting now [with Makhachev], and I think the story is going to be completely different. I don’t remember walking out for that fight. I don’t remember anything. Sometimes you’re looking for something to say about it, but there’s nothing to say. Thousands of times I have asked God, ‘Why?’ but it’s in his hands. He knows what to do.”

THE STREET ON which Oliveira grew up, just outside the favelas, is paved now, but it wasn’t when he was a child. He used to run up and down this street in Guaruja, wearing clothes that people from the neighborhood would give him.

His grandmother still lives in the house he grew up in. She’s been there 50 years. Oliveira has the money to move her to a different home if she desired, but they’ve never discussed it. For all the hardship and trouble in this area, there is also a strong community and a lot of love. The people of this neighborhood care for one another and are proud of each other’s accomplishments.

At the end of the road is a market owned by a man named Tonho. As Oliveira takes the short walk from his grandmother’s house to the market, he rattles off stories of everyone who lives there. There are Luis’ trucks, which Oliveira used to wash for money. Juninho’s house is there, which we helped remodel. Before Oliveira arrives at the market, he stops at a small shop across the way and hugs an older man sitting outside. A trio of young boys sits in the back of the truck, watching Oliveira from afar.

On the side of Tonho’s two-story market is a giant mural of Oliveira’s face. The Brazilian flag waves behind him, along with the UFC’s lightweight belt. The community surprised Oliveira with this painting after he won the championship in 2021. Many years ago, in 2009, the community held a raffle in front of this same storefront to raise money to send a then-19-year-old Oliveira to the U.S. for the first time so he could compete in an MMA promotion in Atlantic City.

“I feel very happy here,” Oliveira says. “Everyone knows my story, and I know their story. This is Charles ‘do Bronx’ [meaning ‘from the favela’]. A boy who came from the bottom.”

On evenings when Oliveira fights, this street fills with residents. His grandmother and aunt set up a screen in front of the house so that the whole community can watch. There are videos of kids jumping and screaming on top of the cars parked along the side. His aunt refuses to watch the fight live but always runs toward the screen when she hears the shouts of celebration.

During fight weeks, Ozana and Francisco fast along with Oliveira, to mimic his difficult weight cut. His grandmother sends him a voice note on his phone, which he listens to repeatedly before the fight. When Oliveira signed with the UFC in 2010, his father told him he was actually living two dreams, not one — his own, but also his father’s. Over the years, Oliveira has come to understand it goes even beyond that.

“Man, I think in reality, all of us who lived here — uncle, aunt, father, mother, grandmother, everyone on the same lot, in the same house — everyone knew what I wanted,” Oliveira says. “So, everyone lived that same dream, you know? When I would go to fight, everyone knew the struggle. There’s just no way everyone wouldn’t be in it together now. Every win for Charles is a win for the whole family.

“And today, I say Charles is global. All over the world, there are people cheering me on. So definitely — my victory is for many, and my defeat is for many.”

The UFC belt has to be in Oliveira’s possession again if he wishes to fulfill the image of that mural entirely. And to do that, he’ll have to beat Tsarukyan on Saturday and then win a rematch in which virtually everything went wrong in the first fight. Oliveira’s strategy to eventually beat Makhachev is unique. He intends to do everything the same. Same camp. Same weight cut. Same game plan. Only this time, he’ll show up on the night of the fight in a way he didn’t for the first.

“It wasn’t Charles in there [the first time],” said Diego Lima, Oliveira’s coach at Chute Box. “We talked to Charles and his family and everyone said he wasn’t himself that day. We had a good strategy, and he didn’t do it. I just think every fighter has good days and bad days. I’ve learned that with Charles and every athlete here. They have their own lives and their own stories. Sometimes you just can’t understand it.”

The odds are undoubtedly against him. If he does get back to Makhachev, he will face as formidable a champion as the UFC has. Makhachev has lost once in 13 years of competition.

As Oliveira looks up at the mural his community created, he smiles. A UFC champion, from an unpaved dirt road among the Brazilian favelas. He’s not afraid of overcoming the odds.

“Nothing and nobody will beat me more than life already has,” he says, staring at the image of the belt. “It’s going to repeat itself again. God would not bring me back to this place only to fail.”