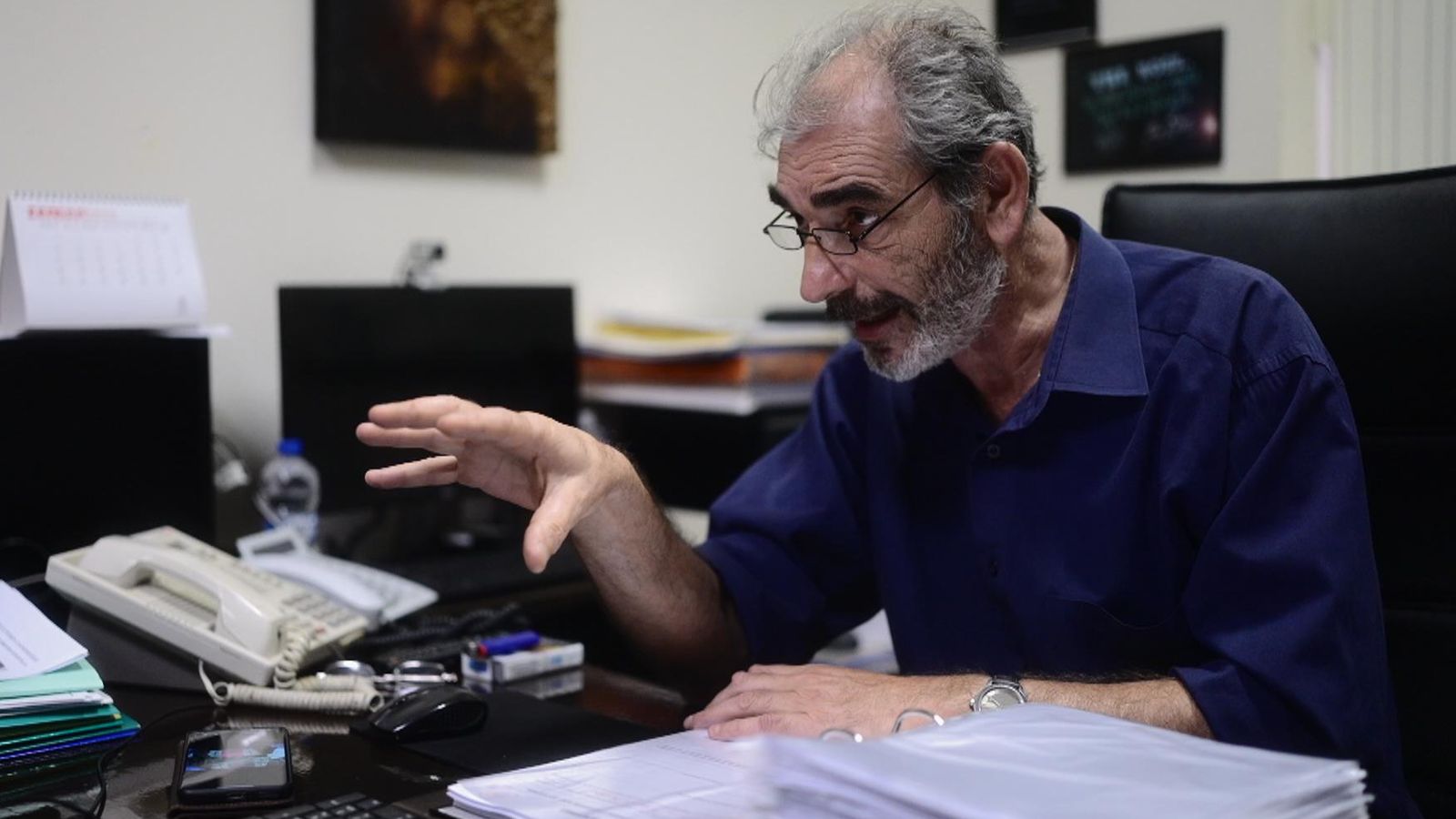

Pavlos Pavlidis leans back in the chair of his office, surveys several cardboard boxes on his desk and takes a deep draw of one of many cigarettes.

Pavlidis is a coroner at the hospital in Alexandroupolis, in northern Greece.

Since he started working here in 2000, he’s been carrying out post-mortems on migrants who’ve died trying to get into Greece, and then attempting to identify them.

“The cause of death is normally obvious,” he tells me. “The problem is finding out who they actually were.”

Within minutes of meeting him, he’s showing me photos to illustrate the difference between those who have died from drowning and hypothermia.

They are not for the squeamish, but he insists people should understand just how dangerous these crossings are.

“All these people – they were killed by migration,” he says.

He conducts a post-mortem to establish the causes of death (“it’s normally obvious,” he says, with a shrug) but Pavlidis also dutifully catalogues ways that the victim might be identified.

Some carry passports, but these gradually disintegrate in the water, along with other paper documents.

All possessions are kept in sealed bags

The clothing they were wearing when found is photographed and so too are any tattoos or items of jewellery.

Everything is kept in a bag, marked with a unique reference number that tracks their case, from the first police report until eventually, a gravestone.

The bodies are kept at the hospital, either in a special area of the morgue or in refrigerated units that are, incongruously, positioned on a service road outside the building.

The idea is to hope that someone, somewhere, will register a missing person, get shown a photo of clothing or jewellery and come forward to put a name to the body.

The bags of possessions are in the boxes on Pavlidis’ desk, carefully sealed and kept for the day when a relative might suddenly appear.

Some are distinctive – a wooden crucifix pendant taken from a man who drowned; a bracelet proclaiming, “I BELIEVE”; notes from friends and family.

There is a baby’s dummy in one bag.

Pavlos believes that, occasionally, a family can be reunited with the body of the loved one they lost, that he can deliver closure: “An answer, even if it’s a bad answer,” as he calls it.

And then, as we talk, two people arrive outside his office – a Syrian family who now live in Germany.

A year before, their brother had tried to get into Greece from Turkey.

Those with him said he reached dry land, but then thought he heard shooting, and jumped back into the water to hide.

The catastrophic problem was that the man was wearing all the clothing he could carry, and the water soaked them immediately. He drowned.

His sister contacted the Red Cross, who had already received photos from Pavlidis.

And one of those photos – of a distinctive zip-up jacket – looked familiar. It was her brother’s.

‘The body is outside in the refrigerator’

They come and sit in the office.

Pavlidis, calmly and with little ceremony, confirms some details.

“The body is outside in the refrigerator”, he says.

He shows them a photo. “Look at these shoes?”

“Yes, yes,” says his sister, through tears.

Another photo, this time of the clothing. Another nod. More quiet sobbing. It’s clear that it’s their relative, but they must be sure.

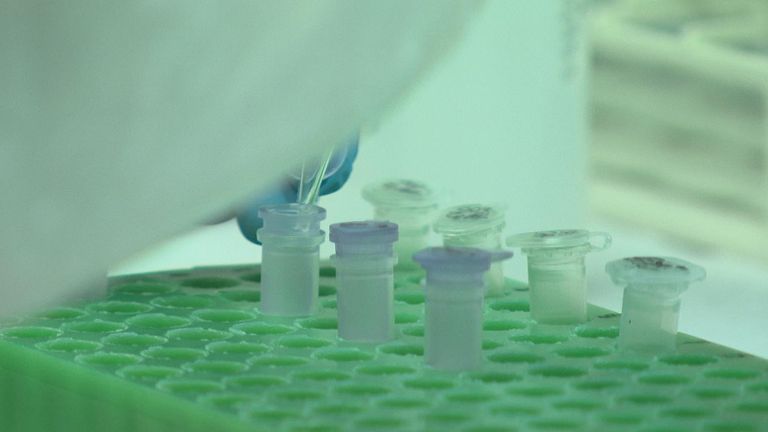

So, the woman is told to provide a DNA sample – a swab taken from inside her cheek and a few drops of blood from her finger.

It will be compared with the DNA sample taken from the body.

But the process is not quick. Pavlidis expects it to take a month.

The family, weary and glassy-eyed, had hoped for an answer within a couple of days.

“It will be him – I am 99% sure,” says Pavlidis, after the relatives have left.

On his shelves are 24 lever-arch files – one for each year since he started keeping records back in 2000.

“My focus is on the relatives, on doing what is best for them,” he says.

“The relatives must know what happened. It is…”, he pauses, “ethical.”

‘The Mediterranean is becoming a mass grave’

Thousands have already died this year crossing the Mediterranean to try to get to Europe.

“Europe has the highest number of dead and missing migrants in the world,” says Kathryne Bomberger, director-general of the International Commission for Missing Persons (ICMP).

“The Mediterranean is becoming a mass grave on a scale that has not been seen in the world before.”

The ICMP has long been at the forefront of using DNA to try to track down missing people, pioneered following the most appalling excesses of the Bosnian war.

“We started using DNA because of Srebrenica,” she says.

Now, they pursue people who have gone missing because of natural disasters, war, trafficking, crime, human slavery or, of course, migration.

They have helped to identify more than 20,000 people over the years.

Sometimes, after a natural disaster, a government will do everything it can to help arrange identification.

But when it comes to putting a name to migrants who’ve died while trying to get into Europe, the support is not there.

It is, says Bomberger, “an ad hoc” process: “I’ll be honest with you, there is no mechanism. All the things we hoped would be put into place still don’t exist.

“Every time there is a disaster like the ship that went down off Greece, we all scramble.”

‘We have a million ideas, but… it’s politics’

What she wants is structure and organisation, with the ability to share data and buy-in from governments.

“The DNA mechanisms and the data systems exist. We have a million ideas about how to ensure co-operation, but the governments need to take responsibility…it’s politics.”

So instead, like Pavlidis, she perseveres – working and waiting, helping and hoping.

An hour’s drive from Pavlidis’s busy hospital, and we are standing in a cemetery at the end of a dusty track on the outskirts of a remote Greek village.

The sun is setting, and the weeds are tall.

A praying mantis is idling on a leaf by my feet.

And all around us are hundreds of graves occupied by people who never saw this place in their lives.

Read more:

61 people found dead off Libyan coast

Asylum seeker dies on Bibby Stockholm

Increasing number of asylum seekers being granted work permits

Everyone buried here was a migrant, who died while trying to cross the nearby border with Turkey and so reach the promised land of the European Union.

And almost all of them are anonymous, their graves marked only by roughly-shaped stones covered in a rudimentary whitewash.

This is a cemetery of the unknown.

But each grave comes with a number, a story and a paper trail.

Look into these numbers, and you can find out where the body was found, how the person died, whether they had any distinguishing features, what they were wearing.

The clues that might just lead to a name appearing on those blank headstones someday.

At one end of the cemetery, praying quietly, is Mehmet Serif Damadoglu.

For decades, he was the Imam and he still lives here, in Sidiro.

It was he who oversaw hundreds of ceremonies at the local mosque, where migrants’ bodies were wrapped, blessed and then taken for burial.

The small local cemeteries began filling up and the locals complained that they would have no space left for their own families, so Damadoglu helped to set up this new burial ground outside the village.

It is used only for migrants’ graves and there are now more people buried here than there are residents living in the village.

He is a man blessed with an easy smile and an enduring sense of faith in the world.

“For us, all that matters is that they were fellow human beings, and therefore they deserve our respect. That’s all. No matter where they came from, they are human beings.

“Whoever comes looking for their relative, we know that they lie there, in that cemetery. It is exclusively for them.

“The burial rituals we perform on them, there is no discrimination. All the rituals I performed for my father and my mother, the exact same rituals we perform for the migrants. They are neither inferior nor superior. We are equal.”

It’s an ideological position that has not always gone down well.

He tells an extraordinary story of holding a service for a young man whose body was badly decomposed.

The village opposed it, saying it was unsanitary and that, if it had to take place at all, it should be rushed.

Damadoglu was resolute: “I said to them – what if this was your son? Would you stop me?”

And then, on the day of the burial, the man’s sister arrived from Somalia.

The Imam told her not to open the shroud, to remember him as he was, but instead she undid the stitches and hugged her brother’s remains. It was a moment of closure – rare but precious.

And that is the hope that is symbolised by this cemetery on a hill. Blank gravestones that are waiting for a name.