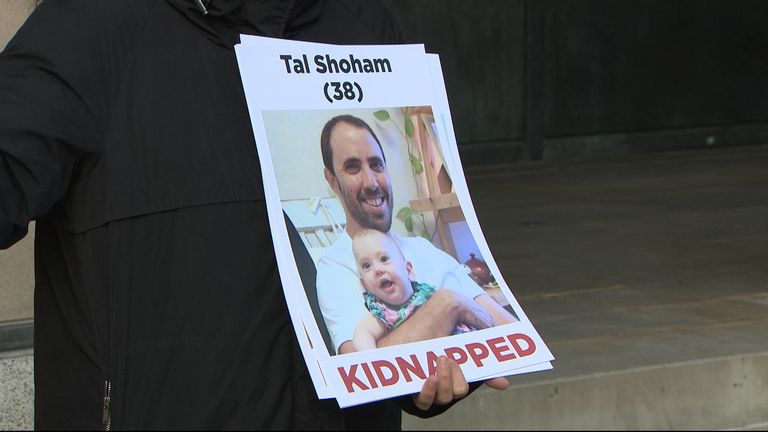

Hamas’s attack on Israel has given rise to the largest-scale hostage crisis in the country’s 75-year history.

About 200 people have been captured and taken into Gaza, according to the Israeli military.

Over the course of the Arab-Israeli conflict, armed Palestinian groups have taken dozens of Israelis captive.

The vast majority have been Israeli Defence Force (IDF) soldiers, which have been used by various Palestinian groups to secure the release of thousands of Palestinian prisoners.

This time, Hamas officials have demanded the release of 6,000 people from Israeli prisons in exchange for the men, women and children taken since 7 October.

While its western allies have strict policies on never negotiating with hostage takers, Israel takes a different view.

Here Sky News looks at Israel’s complex history with hostage negotiations and how it has dealt with similar incidents in the past.

‘Unwritten contract’ between Israel and its people

The taking of hostages has long been a feature of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Armed Palestinian groups have used Israel’s commitment to its people as a bargaining measure to achieve their aims since people were displaced and many killed in the ‘Nakba’ of 1948.

Dr Melanie Garson, associate professor in international conflict resolution and security at University College London, says: “They know the value Israel has always placed on every single life and the explicit promise between the government and the people that they would never leave anyone behind enemy lines.

“That comes from being a very small state fighting for its existence and from the Holocaust when so many people were left unknown.”

Read more:

Plea from families of Israeli hostages

What we know about so far about hospital strike

What is the two-state solution?

The state’s “unwritten contract” with its people also has origins in Jewish law.

The Amidah, a prayer recited three times a day by practicing Jews, refers to God “freeing the captives”. Jewish scripture also prioritises freeing prisoners above feeding the poor.

And safely returning hostages, even those not alive, means the appropriate burial rituals in Judaism can be respected.

Munich massacre

One of the most famous incidents involving Israeli hostages was during the Munich Olympic Games in 1972.

It was carried out by eight members of the Black September organisation, a militant Palestinian group formed in 1970 that took its name from the war between Jordan and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO).

They broke into the Olympic village and at around 4am on 5 September they reached where the Israeli team were staying.

As they drew their weapons a German wrestling judge Yossef Gutfreund tried to intervene and was shot dead.

Two Israelis were killed and nine others, including athletes and coaches, were taken hostage.

The hostage takers’ demands were the release of 234 Palestinian prisoners, as well as members of the German terror group Red Army Faction (RAF), and a plane to take the hostages to an Arab country.

The German and Israeli authorities provided vehicles to take them to a NATO air base where they could then travel by helicopter.

But in a failed rescue attempt all nine hostages and five of the assailants were killed.

Israel launched a military offensive, which they named ‘Wrath of God’, in response four days later. PLO bases in Syria and Lebanon were bombed and 200 people were killed.

Entebbe

Four years later on 27 June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by three men and a woman who were members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and RAF militant groups.

The plane refuelled in Benghazi, Libya, before disembarking in Entebbe, Uganda, at 4am the next day.

All 258 people on board were taken to a disused airport terminal under the watch of Ugandan soldiers.

Initially, 47 elderly people, women and children were released, followed by about 100 non-Israelis.

Around 100 Israelis were left, whom the hostage takers said they would let go in exchange for 53 prisoners.

The Israelis refused to negotiate and instead, with the help of Mossad intelligence and the Kenyan authorities, they organised a rescue operation.

Codenamed Operation Thunderbolt, it was led by Benjamin Netanyahu‘s brother Yonatan.

The raid was successful – almost all of the hostages were rescued and all seven of those holding them were killed.

The only Israeli casualty was Yonatan Netanyahu.

Gilad Shalit

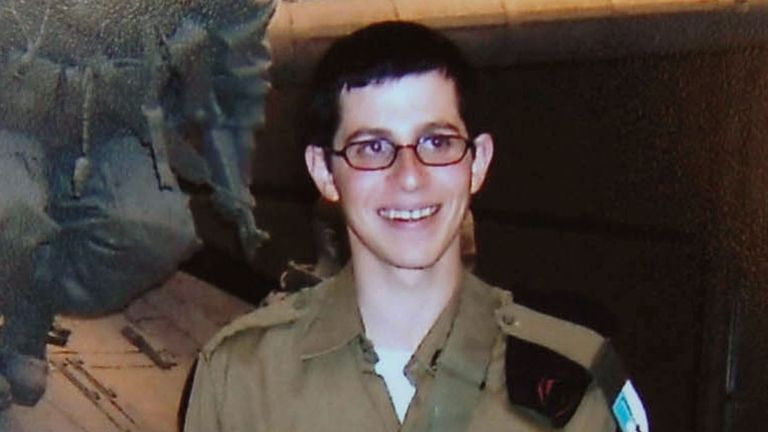

The most recent high-profile Israeli hostage was in 2006 when 19-year-old Gilad Shalit, an IDF soldier, was captured in an attack on the post he was stationed at close to the Egyptian and Gaza borders.

After two tank operators were killed and a third wounded, Mr Shalit was taken into Gaza via Hamas-dug underground tunnels.

He was held by members of Hamas, the Popular Resistance Committees, and the Army of Islam over a period of five years.

His family’s campaign for his return spread around the world, with his father impressing on the Israeli authorities: “The government sent Gilad to fight. It must bring him back.”

Mr Shalit was released on 18 October 2011.

It was the first time an IDF soldier had been returned alive since 1985.

The prisoner exchange was also the largest in history – almost 1,000 Palestinian prisoners were released over the next two months.

During his time in captivity, there were heavy bombardments in both Israel and Gaza.

Past ‘no precedent’ for predicting this outcome

In the past, when there has been enough intelligence to show hostages’ exact whereabouts, the Israelis have launched rescue operations.

But these are very high-risk and with Gaza’s high population density and network of underground tunnels, it may prove impossible to locate those currently being held hostage.

This leaves negotiation.

Nimrod Goren, senior fellow for Israeli affairs at the Middle East Institute, tells Sky News that foreign nationals and women, children and elderly, could be let go as they were in Entebbe.

“Lots of other nationalities being among the hostages could be helpful,” he says. “It increases the interest of other countries – you already have the US, Germany and France offering to help.”

He adds that Israel’s control over humanitarian corridors into Gaza could also be used as a bargaining chip.

But Professor David Tal, chair of modern Israeli studies at the University of Sussex, says the current situation is so “beyond” the usual parameters of the Arab-Israeli conflict that there is no way of predicting how either Israel or the hostage takers will act.

“The nature of this attack is so atrocious, so brutal, it means the past isn’t a precedent that can tell us how it will turn out,” he says.

If the Israelis do negotiate on prisoner releases, it will be through a third-party mediator, possibly Qatar, Egypt or Turkey, as there are no direct lines of communication with Hamas, he adds.

But with Mr Netanyahu’s government vowing the total eradication of Hamas – there could be no one left to negotiate with.

Professor Tal is also sceptical of Hamas agreeing to a release in exchange for humanitarian aid for Gaza.

“Hamas uses its own people as bargaining chips,” he says.

“They want to see human catastrophe in the Gaza strip – they’ll want to prevent humanitarian corridors opening so they can further act against Israel. So I don’t think you can talk about rules or common sense in this case.”